Editors' Note: This article covers a stock trading at less than $1 per share and/or with less than a $100 million market cap. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

PharmAthene (PIP) is poised to jump. Three recent developments have affected its stock price:

- the flu product of its prospective merger partner (Theraclone Sciences) failed to reach its clinical trial's primary endpoint, after which the Department of Health and Human Services' Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) declined funding;

- PharmAthene terminated its merger with Theraclone; and

- the FDA placed a clinical hold on SparVax, PharmAthene's anthrax product.

There has also been a lack of news about the seven-year legal battle with SIGA Technologies (SIGA).

PharmAthene's prospects are rosier that they seem. Below I place each of the bulleted developments in context, and describe and interpret the legal briefs that both sides submitted on December 11. I then derive implications of all of these developments for PharmAthene's stock price.

The Termination of the Merger

I start with the merger, because if there is no merger, then there is no need to read about Theraclone's flu product. I wrote about how the synergy from combining the two companies' mission, strategies, organizational leadership and portfolios would enhance shareholder value here, and believe that the benefits to each side argue in favor of a merger. Before explaining why I still think a merger might be still on the table, let's review the three reasons that it was terminated.

By far the most important reason is the initiative taken by Prescott Group Capital Management, who owns more than ten percent of PharmAthene's stock. As they wrote in a letter to shareholders (emphasis theirs):

We believe that PharmAthene's SIGA litigation asset is hugely valuable and little credit for that value is given in the merger. How can the company's own "fairness opinion" adviser value all of PharmAthene at only $1.72 a share? PharmAthene properly notes in its own proxy statement that it has taken the position in Delaware court that its damages "may be as high as $1 billion dollars" (proxy page 36). For the proposed merger transaction with Theraclone, however, PharmAthene has taken the position that its SIGA litigation is worth only about 5% of this amount. According to the Proxy Statement, to reach this conclusion PharmAthene's financial advisor used a 100% probability for all of SIGA's positions as to cost allocations and revenue timing, as well as a 0%probability of any orders, domestic or foreign, beyond the very base term of the drug's current government contract (proxy page 102).

Shareholders are likely to become even more convinced that this "asset" is undervalued after reading my discussion below of what is in the latest briefs.

The second reason is also financial. PharmAthene will probably not receive any money from SIGA until July 2014 at the earliest. Theraclone has a serious cash shortage, and if the merger had been approved, it is possible that PharmAthene's financial position would become compromised in the short run, requiring it to make disadvantageous financial arrangements.

The final reason is the failure of TCN-032 to reach its endpoint in its Phase IIa trial and BARDA declining to invest in subsequent trials (discussed below).

In sum, the first reason is that PharmAthene seemed undervalued, the second was that an imminent merger with Theraclone seemed to represent a threat to PharmAthene's short term financial health, and the third was that the clinical trial results coupled with BARDA's lack of financial support seemed to imply that Theraclone was overvalued. Although I voted for the merger, I think that the first two of these reasons are valid. The merger termination news briefly lifted PharmAthene's stock price, until the press release about SparVax.

However, because of the positive reasons for merging, including the information disclosed about TCN-032 below, I hope and suspect that there is still mutual interest in renegotiating the merger once there is greater clarity regarding the litigation outcome. PharmAthene still wishes to increase its portfolio and market opportunities, and for the next six months, Theraclone's cash needs have increased. After Vice Chancellor Donald Parsons of the Delaware State Court of Chancery issues his ruling (probably in February 2014), the conditions for negotiating more favorable terms will be much clearer. If SIGA appeals to the Delaware Supreme Court, the dust will probably settle by July.

Theraclone's Flu Product Clinical Trial Results

To understand the significance of the TCN-032 missing its endpoint, it is important to recognize that Phase II is sometimes divided into two steps. When it is, Phase IIa is a smaller, less expensive clinical trial that has two goals: assessing dosing requirements, and learning more about how the product impacts humans along a variety of dimensions, which is important when new mechanisms of action are involved (as is the case with TCN-032). As a result, when the larger, more expensive Phase IIb is launched to assess the effectiveness of the product at the key dose level(s), the investigators can select outcome targets that maximize the chances of success.

For Phase IIa, Theraclone's researchers had selected a challenging endpoint: reducing the proportion of subjects who developed any grade 2 (G2) or greater symptoms or fever. Theraclone believed a clinical (as opposed to a viral) endpoint was more suited to TCN-032's mechanism of action. PharmAthene spokesperson Stacey Jurchison explained that the primary endpoint chosen was "a bright line in the sand": whether or not, throughout the course of the study, a patient had any G2 events, which include headaches, a common flu symptom. She said, "Some TCN-032 treated subjects who were not very sick (low symptoms and no viral shedding) reported G2 symptoms (headache most often). Some placebo patients who were very sick (high total symptom score and high viral titers) never reported any G2 symptoms. Therefore, choosing such a bright line in the sand (any single G2 symptom over the course of the study) created a very high hurdle."

The Phase IIa data for TCN-032 showed a positive trend, but did not reach statistical significance for the primary endpoint. On the one hand, BARDA's decision to decline to provide additional R&D funding for TCN-032 was not surprising, given that, like the FDA, its criterion is whether or not clinical tests meet their pre-established primary endpoints.

On the other hand, important secondary endpoints were achieved, showing that TCN-032 is effective in reducing clinical symptoms and viral load. Jurchison indicated that Theraclone has had extensive discussions with a group of key opinion leaders in the influenza field who were very encouraged by the Phase 2a results. Based on these discussions, Theraclone is very enthusiastic and encouraged to continue clinical investigation of TCN-032 and, possibly with financial support from its Japanese partner Zenyaku Kogyo, plans to begin additional Phase 2 testing next year with primary endpoints selected on the basis of the recent study. If, as is likely, the next Phase II study meets its primary endpoints, BARDA will reconsider.

In my opinion, TCN-032 is a valuable asset. Its promise is worth pursuing, but its initial failure to meet the original primary endpoint gives PharmAthene more leverage should merger negotiations with Theraclone resume.

The FDA's Clinical Hold on SparVax

We saw this movie once before. Before the clinical Phase II trial was underway, the FDA placed it on hold pending the provision of additional stability data and more information on PharmAthene's latest stability indicating assay. After PharmAthene submitted the requested information, the FDA lifted its clinical hold. The Phase II trials have not yet started, so this new clinical hold is not based upon any adverse effects. The FDA will explain its hold by January 15, but it is important for investors to keep the following facts in mind:

- SparVax was developed for both pre- and post-exposure.

- It can rapidly be scaled-up, has enhanced convenience (because it is packaged in prefilled syringes), and has already successfully completed Phase I and Phase II trials, which demonstrated that SparVax is at least as safe and effective as BioThrax. However, because the previous Phase II studies were carried out with SparVax that was manufactured in Great Britain, the FDA is requiring PharmAthene to conduct a Phase II trial on SparVax that has been manufactured in the U.S.

- The proportion of subjects experiencing pain at the injection sire was more than double for those receiving BioThrax as receiving SparVax.

There is no reason to expect a different result in the U.S. trials. So far, PharmAthene has received funding of $213 million for SparVax if all milestones are met and the U.S. Government exercises all options under the contract.

New Developments in the SIGA Litigation: The 12/11/13 Briefs

First, four paragraphs of context. Like PharmAthene, SIGA Technologies is a biodefense company. Its major product is Arestvyr, SIGA's smallpox product, which used to be called ST-246. SIGA has a major contract with BARDA, the organization within HHS that provides an integrated, systematic approach to the development and purchase of the necessary vaccines, drugs, therapies, and diagnostic tools for public health medical emergencies. It calls for SIGA to deliver two million courses of Arestvyr to the government's Strategic National Stockpile, and SIGA expects to complete its delivery during 2014.

As followers of the two companies know, PharmAthene and SIGA signed two "Type II" agreements, both of which contained language obligating each to "negotiate in good faith with the intention of executing a definitive License Agreement in accordance with the terms set forth in" a License Agreement Term Sheet ("the LATS"). If the two parties had successfully consummated such an agreement, then PharmAthene would control the license for Arestvyr. Vice Chancellor Parsons found, and the Delaware Supreme Court affirmed, that SIGA not only breached its contractual obligation to negotiate in good faith, but in doing so exercised bad faith. The second part of this finding is important because "Under Delaware law, bad faith constitutes 'not simply bad judgment or negligence, but rather ... the conscious doing of a wrong because of dishonest purpose or moral obliquity; it is different from the negative idea of negligence in that it contemplates a state of mind affirmatively operating with furtive design or ill will'" (p.53, Vice Chancellor's 2011 ruling, inner citation omitted).

Lumping together two different rationales (one based on a breach of a contractual obligation to negotiate in good faith and the other based on the doctrine of promissory estoppel), the Vice Chancellor imposed a damages award that for a ten-year period, evenly split between the two companies any profits from Arestvyr that exceeded $40,000,000. The Supreme Court ruled that when a party breaches a Type II contractual obligation to negotiate in good faith, it is permissible for a judge to impose expectations damages. However, because it also ruled that the doctrine of promissory estoppel did not apply to this case, it remanded the damages award to the Vice Chancellor because it was not clear upon which legal rationale his award was based. The Supreme Court called for the Court of Chancery to impose a remedy whose rationale solely related to breaching a Type II contractual obligation to negotiate in good faith.

In June, PharmAthene and SIGA met with the VC, submitted briefs regarding whether the record of facts could be reopened, and exchanged briefs during July. The Vice Chancellor ruled that he would allow the record to be reopened as long as any new material related to the items that PharmAthene wanted to include and those that SIGA wanted to use to rebut those provided by PharmAthene. He reserved the right to rule later that some of the evidence should not be added to the record. The briefs that each company submitted in December have given both companies the opportunity to add to the record and to articulate their final arguments. Each will be able to respond in writing to the other's brief and participate in an oral hearing on January 15.

Seven Arguments

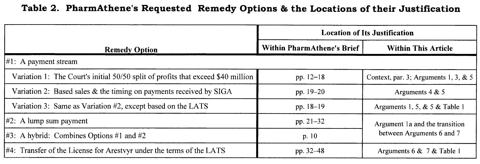

Below, I describe six arguments that SIGA raises (numbered 1 to 6 solely for rhetorical purposes, given that SIGA introduced them in a different sequence and made other arguments I either don't discuss or subsume under these six). For each, I (1) explain why the argument matters to PharmAthene, and (2) assess its merits, sometimes citing PharmAthene's counterarguments. After discussing all six of SIGA's arguments, I present a table that sets forth each remedy option that PharmAthene is asking the Court to consider, along with the location of its justification, both within PharmAthene's brief and within this article.

Then I turn to Argument #7, PharmAthene's game-changing argument in favor of its preferred remedy option: "specific performance." I discuss both its importance and why I believe it will prevail. The bottom line is that if the VC agrees that the Court should order the transfer of the license to PharmAthene under the terms of the LATS. Assuming SIGA appeals the order, if the Supreme Court upholds the Chancery Court, then the remedy imposed during this final round will be better for PharmAthene than before, not only financially but also in other respects.

SIGA's Argument #1: Expectation damages are not available because they would be speculative (p. 20). Whether the Court can impose expectation damages is important to PharmAthene because, according to SIGA, the only alternative to expectation damages is reliance damages (There is one more alternative which SIGA discusses in Argument 6). Reliance damages would mean that PharmAthene would not participate in Arestvyr's success. It is an old argument that the Vice Chancellor already ruled against in 2011. I have thoroughly explained here why this argument won't prevail in Delaware's Supreme Court. However, SIGA has come up with two new twists, both of which require additional analysis.

- Variation #1a: "The Vice Chancellor's ruling "that expectation damages are speculative...is the law of the case" (p. 17). First raised in SIGA's July 30 brief, Variation #1a ups the ante because it asserts because the Vice Chancellor himself concluded expectation damages were too speculative (and because the Supreme Court did not object to his conclusion), by the "law of the case" doctrine, he may now impose an expectations award. To buttress its claim, SIGA quotes the Vice Chancellor's 2011 ruling: "Having carefully reviewed the testimony and reports of PharmAthene's experts..., I find that PharmAthene's claims for expectation damages in the form of a specific sum of money representing the present value of the future profits it would have received absent SIGA's breach is speculative and too uncertain, contingent, and conjectural" (p. 94). As I described in detail here, SIGA grossly distorted what the Vice Chancellor said. As you can see from re-reading the quotation, what he said was that one form of expectation damages would be too speculative, namely, "expectation damages in the form of a specific sum of money representing the present value of...future profits." In fact, in the 2011 opinion, having rejected one form of expectation damages, he imposed another form (the income stream). Accordingly, SIGA is simply wrong that the Vice Chancellor said that expectation damages are speculative in any form.

- Variation 1b: Even PharmAthene admits that estimating revenue from Arestvyr is too speculative (p. 14). In SIGA's view, the smoking gun is the registration statement filed with the SEC in connection with the Theraclone merger. The key quote is that "there is significant uncertainty regarding the level and timing of sales of Arestvyr, and when and whether it will be approved by the U.S. FDA and corresponding heath agencies around the world." Although SIGA buttresses its arguments by quoting details from PharmAthene's SEC filing, PharmAthene was protecting itself from potential suits from both its own investors and those who had invested in Theraclone. The crucial issue regarding the speculative nature of expectations damages awards is whether such an award is speculative if it is in the form of an income stream tied to actual Arestvyr-generated income. Vice Chancellor Parsons ruled that it was not, and when the Delaware Supreme Court had the chance, it didn't comment one way or the other.

Although SIGA argues that expectation damages are not available, because the Supreme Court explicitly said that they are available for this kind of a breach (provided that restoration of loss profits is not speculative), SIGA has hedged its bet via Arguments 2-5. Each tries to limit the Court's ability to impose an expectation damages award.

SIGA's Argument #2: The BARDA contract can't be a part of an award because "expectation damages are calculated as of the breach, and the BARDA contract was not and could not have been known as of December 2006" (p. 22). For the Court to have the capacity to base at least part of an expectation damages award on the BARDA contract is important to PharmAthene both because it is the only existing contract involving sales of Arestvyr, and because the procurement portion of that contract is worth approximately $409 million.

However, SIGA isn't quoting the law accurately. There is a big difference between calculating expectations as of the breach and determining the nature of the expectancy interest and providing a remedy for that loss expectancy. As Vice Chancellor Parsons explains, the legal requirement has two steps: first "to determine PharmAthene's expectancy interest, and, second, to provide a remedy that reasonably compensates PharmAthene for that lost expectancy" (p. 101, 2011 ruling). Furthermore, in its brief (p. 27), PharmAthene quotes the Delaware Supreme Court as saying that the Court may consider events that took place after the date of the breach "in order to aid in its determination of the proper expectations as of the date of the breach."

More important, PharmAthene argues that:

- from what was known at the time of the December 2006 breach, and taking into account SIGA's own assumptions and projections, PharmAthene's expectations damages were worth over $1 billion;

- the expert who prepared the 2007 analysis supplemented his report three years later with information "based on SIGA's own cost, price and delivery schedules...[that had been] contained in its BARDA submissions" (p.29); and

- a summer 2013 analysis by a different expert makes clear that the original expert's estimate was based upon assumptions that "were extremely conservative and borne out by subsequent events" (p. 30).

SIGA's Argument #3: If the Court does impose the same award it did last time, it should split profits not after the first $40 million, but after the first $80 million (p. 11, Footnote 7). Although this is the least important argument that I shall discuss, it matters to PharmAthene because if the Court imposes a similar form of damages as last time but excludes the first $80 million instead of the first $40 million, then PharmAthene loses $20 million that it would have received if the Supreme Court upholds this form of damages award.

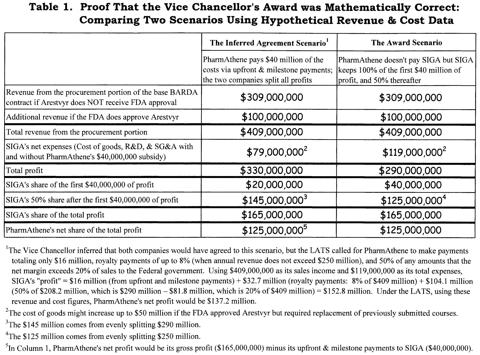

SIGA claimed that the VC erred "because an $80 million offset (i.e. 2X the payment amount) was necessary to reflect an absent payment from PharmAthene to SIGA in the context of 50% profit-split payments by SIGA to PharmAthene" (both the underlining and the parenthetical expression were in SIGA's footnote). I will not try to make SIGA's point more comprehensible, because it is SIGA that has made a mathematical error. There is no need to double the $40 million, since the award gave SIGA 100% of the first $40 million of profit.

Table 1 contains hypothetical but empirically-based revenue and expense figures in order to (1) demonstrate the mathematical correctness of the Vice Chancellor's reasoning, (2) show what I think the BARDA contract is worth to both SIGA and PharmAthene, and (3) compare and contrast the VC's award with the economic terms in the LATS (which becomes relevant in the discussions after Argument 6). Focusing solely upon the mathematical demonstration, Table 1 shows two scenarios. VC Parsons found that both sides would agree to Scenario 1, where PharmAthene pays SIGA $40 million in upfront and milestone payments and equally split all profits. His award was Scenario 2, with SIGA keeping the first $40 million of profits and then equally splitting all subsequent Arestvyr-based profits. The last line in Table 1 shows that SIGA's profit under both scenarios is identical.

SIGA's Argument #4: The record law provides no basis for awards that includes a percentage of sales (p. 26-27). This claim is relevant because among the options that PharmAthene is vigorously pursuing (see its brief, pp. 19-20 of) is one that changes the basis of the award from profits to sales. The first part of SIGA's assertion is that determining a percentage of sales requires data about costs, but the only information that is on the record has to do with past, current, and future revenues. The second quarter 10Q is on the record, and it might be possible for the third quarter 10Q despite the VC's bench ruling on August 15 that PharmAthene's evidence "would be limit[ed] to what is available right now."

The reason that the VC might reconsider his bench ruling is that PharmAthene has painted a sordid picture of the steps SIGA took while the Supreme Court decided whether or not to uphold the VC's damages award. They prepared a schedule to which they attributed so many costs to Arestvyr that it looked like SIGA would make hardly any money on their main asset. In September, SIGA hired Keith Ugone to use this draft to write a report valuing Arestvyr. After reviewing Ugone's report, PharmAthene's own expert concluded that SIGA has chosen "to allocate substantially all R&D and SG&A expenses not directly attributable to ST-246, to ST-246. Consequently, sales of ST-246 are underwriting purported unreimbursed R&D and SG&A expenses to benefit the corporate structure of SIGA - a reality that results in significant benefit to SIGA that may be inconsistent with the Court's intent . . . [because] it creates an economic incentive for SIGA to invest in R&D and SG&A activities and resources at PharmAthene's expense" (PharmAthene's brief, p.9, citation omitted)

PharmAthene's brief asserts that examining the actual schedule that Ugone relied upon revealed that "all supportive data was missing . . . , leaving only unsubstantiated summary data. Ugone admitted that (1) either the supportive data was redacted from the schedule or the summary data was included on a blank schedule, (2) he did not know where the data on the original schedule originated, and (3) did not ask" (pp. 9-10).

So we have this interesting juxtaposition: SIGA has claimed that the Court can't use a percentage of sales because there are no data on the record regarding costs, and on the other hand it is clear from the data regarding costs that is on the record that SIGA has taken steps both to create an impression that appears to differ from reality and to conceal the data that would allow the Court to draw its own conclusions.

But the best refutation of SIGA's Argument #4 was already mentioned in my analysis of Argument #2: the pre-trial record contained an analysis of cost information that SIGA supplied to BARDA.

SIGA's Argument #5: No case law supports awarding expectation damages in the form of an income stream (p. 27). Having expectation damages available in the form of future income streams is important to PharmAthene because the Vice Chancellor has already ruled that having a lump sum payment in front that represents the entire present net value of what PharmAthene might receive would be too speculative (Note that PharmAthene hopes to prove that there is enough information on the record to justify a hybrid award: part up-front payment and part future income stream).

SIGA asserts that PharmAthene has not cited any case law, that SIGA's attorneys don't know of any, and that Courts wouldn't support doing so because if they awarded damages in that form, they would involve themselves in years of ongoing supervision. SIGA is correct in arguing that Courts don't want to involve themselves in years of ongoing supervision, although the VC's 2011 award called for ten years of Court supervision. But SIGA's main assertion here (that PharmAthene has not cited any case law) is no longer accurate. In its December 11, 2013 brief, PharmAthene cites two Delaware cases: Cura Financial Services v. Electronic Payment Exchange and ID Biomedical v. TM Technologies. The opinion in ID Biomedical was authored by Myron Steele, who also authored the Supreme Court decision in SIGA v. PharmAthene (Steele retired last month to rejoin the corporate world).

SIGA's Argument #6: Equitable damages are not available (p. 28). "Legal" remedies, such as expectations or reliance damages, are available to successful claimants by right (provided that the Court can impose them in an acceptable form). In contrast, equitable remedies are only available by the discretion of the Court. In particular, they are only justified when:

- equities strongly weigh in favor of the injured party, and

- available legal remedies are inadequate or impracticable.

Having equitable damages available is important to PharmAthene because if SIGA convinces the Court that neither expectation damages nor equitable damages are available, then the only alternative is reliance damages. Under the doctrine of promissory estoppel, equitable damages are clearly possible. However, recall that the Supreme Court remanded the damages award to the Vice Chancellor with instructions to impose a remedy solely on the grounds that SIGA breached its Type II contractual obligation to negotiate in good faith; it does not want to have the Chancery Court's ruling contaminated by references to the doctrine of promissory estoppel. One of the ways that the VC muddled the waters was by calling the remedy that he imposed (an on-going profit participation in future sales) an "equitable payment stream" (e.g., p. 85). Accordingly, when seeking expectations damages in the form of a payment stream, PharmAthene could use terminology other than “equitable payment stream.” Three options are “expectation damages payment stream,” “sales participation payment stream,” or simply “restoration payment stream.”

What about the requirement of showing that equities strongly weigh in favor of the injured party? This is typically, at least in part, by taking into account the knowledge, state of mind, and motives of the injuring party. PharmAthene has a strong case here. An important standard is whether the injuring party's pre-breach conduct reaches a high enough level of egregiousness. The VC found that SIGA's conduct was "glaringly egregious" (p. 114). However, in its current brief, PharmAthene argues that SIGA has continued to act in bad faith in at least two respects.

- As already described under Argument 4, SIGA has been inappropriately attributing costs to Arestvyr that were not related to the procurement portion of the BARDA contract (Presumably, some of the costs should have been attributed to the R&D portion of the same BARDA contract).

- Citing SEC filings and the transcript of earnings conference calls, PharmAthene provides evidence (see pages 6-8) that SIGA intends to delay recognition of revenue at least until the FDA approves Arestvyr, which SIGA says will not happen until 2017 at the earliest, and might never happen. While SIGA argues that there is no basis for calculating profits until revenue has been formally recognized, it has publicly acknowledged that whether or not the FDA ever approves Arestvyr, it is free to use the pre-FDA approval cash that it receives from BARDA (approximately $309 million) any way that it sees fit. SIGA argues that it has no choice to postpone revenue recognition under GAAP accounting rules. PharmAthene provides evidence that SIGA chose to delay revenue recognition, but was not required to do so.

And what about the condition that equitable remedies can only be imposed if available legal remedies are inadequate or impracticable? Because this condition is especially to "specific performance" remedies, I shall discuss it under Argument 7.

A Pause before discussing the PharmAthene Game-Changer:

A Summary of PharmAthene's Requested Remedy Options

So far, I have discussed three payment stream variations. In an aside, I mentioned that the VC rejected PharmAthene's earlier request for a lump sum payment. Because the Supreme Court remanded the remedy after ruling that although the doctrine of primary estoppel didn't apply but that expectation damages were permitted, it did not consider PharmAthene's arguments about lump sum payments. In its latest brief, PharmAthene presented two new justifications for the VC:

- a rebuttal of to SIGA's claim that PharmAthene's earlier expert's two estimates were wildly inconsistent, and

- an assertion that post-trial evidence confirms the accuracy of the earlier estimates.

But in addition to the payment stream and lump sum options, PharmAthene is asking for two other remedy options:

- a hybrid, i.e., a combination of an up-front lump sum and an ongoing payment stream; and

- "specific performance," transferring the license for Arestvyr to PharmAthene under the terms of the LATS (discussed in Argument 7).

Table 2 summarizes all of these options. It also shows where to find discussions and justifications relating to each, both within PharmAthene's brief and within this article.

Argument #7 (PharmAthene changes the game): The Court should order SIGA to transfer the license for Arestvyr under the terms of the LATS. This is especially important to PharmAthene because securing the license is PharmAthene's preferred option. It would mean that PharmAthene would be able to control the development, approval, and commercialization of Arestvyr and related products. It would also mean that instead of PharmAthene having to depend on SIGA's cooperative spirit or further lawsuits to receive any money, PharmAthene would, as spelled out in the LATS, receive the income from contractors or sublicenses directly. It would then pay SIGA what the LATS said that SIGA is due.

As discussed above, in order for the Court to impose an equities remedy such as ordering the transfer of a license, it must become convinced that equities strongly weigh in favor of the injured party. As mentioned in connection with Argument 6, the VC already arrived at this conclusion before the breach, and evidence has continued to pile up since the brief that the balance has now tipped even more strongly in favor of PharmAthene. PharmAthene must demonstrate the validity of three other propositions. Each is described and discussed below:

PharmAthene is ready, willing, and able to control the license. PharmAthene makes a convincing case that at the time of the breach, (1) it had the personnel, experience, and capacity to develop and market Arestvyr, and (2) SIGA did not. PharmAthene argues that there is still a substantial difference in the qualifications of the two companies to exercise license-related responsibilities. One example is that it took SIGA two years from the time that FDA asked for Arestvyr to be tested on primates, and when SIGA caused trials to begin. Another is that SIGA still subcontracts out many substantial tasks that PharmAthene can perform in house. In that connection, PharmAthene asserts that it had the experience and expertise necessary to deal not only with the transfer of government contracts, but also to take over and manage subcontractors.

Available legal remedies are inadequate or impracticable. SIGA has argued that expectation damages are unavailable (on the grounds that they would be speculative), and the VC has concluded that reliance damages are inadequate. However, the VC concluded that expectation damages were available, and, despite the Supreme Court's remand of the remedy, will probably will reach the same conclusion. So what PharmAthene needs to do is to demonstrate that even a large expectations damages remedy is either inadequate, impracticable, or both. PharmAthene claims that expectations damages would be inadequate on four grounds:

- The economic terms in the LATS were more favorable to PharmAthene. In Footnote of Table 1, I explain why under the BARDA contract, PharmAthene's profit would exceed that under the VC's initial award by $12.2 million. Additional contracts with the U.S. Federal government would be even more favorable to PharmAthene because, under the LATS, there would be no milestone payments, only royalty payments and profit sharing. But the real economic advantage to PharmAthene would come from foreign contracts, which call for the PharmAthene to pay SIGA the same royalties, but has no provision for profit sharing.

- The economic pie would be larger, so both companies would do better. The reason that the economic pie would be larger if PharmAthene controlled the license was described my discussion of the previous proposition (that PharmAthene is ready, willing, and able to control the license).

- Profits are not the only economic consideration. Without the license, PharmAthene was deprived of using government funding to "augment its infrastructure and hire personnel to support both ST-246 and non-246 related activities" (p. 44).

- There are important non-economic considerations that money can't replace. One is "an enhanced reputation . . . as a result of the successful development of a key biodefense medical countermeasure" (p.45).

PharmAthene claims that expectations damages would be impracticable on two related grounds: (1) Given SIGA's past and present conduct, if PharmAthene is awarded expectations damages, it is likely to encounter problems in trying to collect a money judgment, especially one involving an ongoing payment stream; and (2) the extent of supervision required by the Court, and the length of time over which it would need to exercise it would be far more onerous than would be the case if PharmAthene assumed the license and the responsibility to make ongoing payments to SIGA.

Despite the VC's earlier conclusion to the contrary, the LATS contains all elements that the two parties considered essential. In his 2011 opinion, Vice Chancellor Parsons found "that a reasonable negotiator in the position of PharmAthene would not have concluded that the LATS, as attached to the Bridge Loan and Merger Agreements, manifested agreement on all of the license terms that SIGA and PharmAthene regarded as essential" (p. 45). PharmAthene supplements its pre-trial arguments with new ones demonstrating that the elements that have been noted as absent from the LATS are:

- no longer relevant,

- not essential (and not included in comparable license agreements for companies in the biological and pharmaceutical industry), and/or

- could be imposed by the Court.

PharmAthene cites Asten v. Wanger Systems, a Delaware case whose opinion was once again authored by former Chief Justice Myron Steele when he was a Vice Chancellor. The Court said the enforceability of agreements that omitted matters for future negotiation "depends upon the relative importance and severability of the matter left to the future. It is a question of degree to be determined by whether the matter left open is so essential to the bargain that to enforce that premise would render enforcement of the rest of the agreement unfair" (PharmAthene brief, p. 35, internal citation omitted).

This may be the steepest hill that PharmAthene needs to climb, since smart people who have carefully arrived and committed themselves to a conclusion find it difficult to change their position. The following three factors may help convince the VC to reverse his position:

- the Asten test for essentiality of allegedly absent terms provides useful guidance,

- the three years that have intervened make it clearer that the alleged missing terms are indeed no longer relevant or peripheral, and

- SIGA's ongoing bad-faith conduct (1) increases the assault on the Court's conscience and (2) makes the alternative of an expectations damages award both more impracticable and a more onerous proposition for the Court.

In other words, these various principles are intricately interrelated. Vice Chancellors have substantial discretion, and SIGA's conduct continues to motivate Vice Chancellor Parsons to use his.

Conclusion

First, here's my take on the three reasons that PharmAthene shares have recently fluctuated:

- As far as outsiders can tell, the merger with Theraclone was terminated solely because PharmAthene shareholders were dissatisfied with the financial terms. Presumably, the key individuals in both companies still see the synergy. Therefore, the merger is worth pursuing but at a price that properly values PharmAthene's litigation asset, and at a time when PharmAthene can financially support the R&D for both companies' portfolios.

- Theraclone's clinical trial demonstrated that its flu vaccine is effective in reducing clinical symptoms and viral load. It is highly likely that when it conducts its next Phase II trial with empirically-based primary endpoints, the FDA will agree that a Phase III trial is appropriate, and BARDA may then step up to the plate.

- The FDA's clinical hold on SparVax does not signify that any adverse effects have occurred. Because SparVax already successfully completed Phase II trials when the same substance was manufactured in Great Britain, it is highly likely that (1) it will be given the go-ahead to conduct the clinical trials in the U.S., and (2) the trials conducted here will produce the same result as they did in Great Britain.

And here's my take on the outcome and timing of the litigation. I believe that the Court will impose one of two remedies: a hybrid expectations damages remedy, based upon the economic terms of the LATS, but upon (1) sales rather than profits, and (2) the timing of payments received, with the timing based upon when SIGA receives income, not when SIGA chooses to formally recognize revenue. If the Court imposes such an award, I expect the percentage of sales to be at least 40.3 percent, which would yield the figures displayed in Table 1. I hope that in conformance with the LATS, it would have separate basis for foreign sales (Using the cost data in the left scenario of Table 1, under the LATS, PharmAthene would receive 72.7% of the sales price). The other option, which I believe is fully justified, is ordering the transfer of the license for Arestvyr under the terms of the LATS. Furthermore, I believe that the Supreme Court will affirm either remedy, and do so by July 2014.

Within a month after the litigation is finally settled, I predict that PharmAthene shares will at least double. If the merger is then consummated on the basis of PharmAthene's changed financial condition, by this time next year, I believe that each share of PharmAthene will sell for at least $6.00. Both predictions assume sales-based income streams and differential treatment for foreign sales. If SIGA is ordered to transfer the license to PharmAthene, then its shares will do even better.

These are my reasons for believing that PharmAthene shares are currently a bargain, and it is why I increased my holdings earlier this month.

Disclosure: I am long PIP. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article. (More...)

This entry passed through the Full-Text RSS service — if this is your content and you're reading it on someone else's site, please read the FAQ at fivefilters.org/content-only/faq.php#publishers.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire