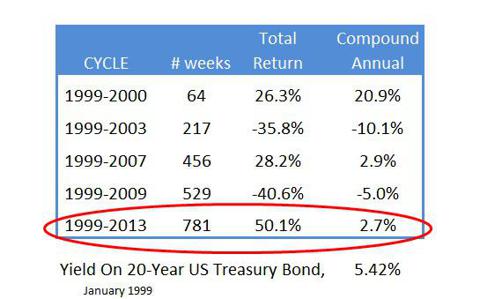

As we ponder 2014's headwinds and reminisce about the bubble/not bubble in stocks, there is one more factor to add to my note from yesterday about the time value of assets. For simplicity's sake I kept all the calculations as nominal; no need to introduce complexity when the elegance of simple math made the point very nicely. Despite record highs in stocks right now, this millennia has seen very little by way of gains - even in strictly nominal terms.

Adding inflation, since you cannot ignore the real world, only makes the performance and behavior of stocks all that much worse. If we assume even a modest inflation rate in the 2000s and so far in the 2010s of about 2%, stocks have generated a 0.7% real compound annual return. This total return of next to nothing, despite record highs right now, assumed far more risk than it has been worth. As I said yesterday, it is the epitome of asymmetry working against you.

Notice the similarities in the table above in the compound annual returns from 1999 to both 2007 and 2013. Even when stocks are at their highs they are barely able to manage the inflation. That was true of the Great Inflation period itself in the late 1960s and 1970s, though it appears that the form of inflation (and even its core meaning) may have "evolved."

This does not mean that you avoid stocks altogether, only that you have to actively manage the risks (meaning work asymmetry in your favor). A full measure of managing those risks is understanding them to the fullest possible extent. That means not only breaking apart the statistical measures upon which we base so much psychological reflection, but also the financial system as it works in the real world apart from the orthodox spreadsheets.

There is another element here in terms of risk that needs to be addressed. The mainstream idea of inflation itself is, at best, incomplete. The concept of a precise measure of all the moving parts of prices in an economic system is beyond complex (technical term). There is a whole lot of hubris in the CPI.

It was interesting to note that there was a great housing crash at the end of the 1970s. Not in terms of prices, mind you, but on a scale of construction activity even greater than what we saw from 2007-2010. But because prices were little disturbed then it bears little remembrance. That would more than suggest a change in behavior occurred between that crash and the one in the 2000s that will be nearly immortalized.

In May 2006, Fed Governor Susan Bies meandered into this dogmatic reflection, noting,

But the fact that inflation continues to be above 2 percent in the forecast period is something that does concern me, and I think part of my concern relates to the tremendous amount of liquidity that sits out there in the banking sector, in the U.S. financial markets, and clearly globally. The presence of this liquidity is something that we really need to think about. It's not back to where it was in my money supply days, when I started my career at the St. Louis Fed; but I do worry that liquidity is, as some of you have said, causing a lot of transactions to occur that economically perhaps wouldn't otherwise occur.

Comparing that partially-formed, and unfortunately forgotten, thought to the 1970s-80s housing bust, you can only come to the conclusion that inflation is more than just prices. I wrote a few months ago about this process as it is not very well understood, let alone measured:

Second, and far more important, such asset inflation carried over time is even more insidious and harmful than consumer inflation. The current model of monetary mechanics posits that the answer to every economic problem is financial. Either through "liquidity" or interest rate psychology, there is always a monetary/debt rejoinder to lead the way into economic robustness. And in each episode, behavior responds by expecting financial results when, in fact, the real economy needs productive behavior - far less home flippers and day traders in favor of far more entrepreneurs looking to harness some industry that actually creates wealth rather than seeking to transfer someone else's.

Stocks are at, or are close, to an all-time high despite economic circumstances that are almost diametrically opposed to such an occurrence. There are certainly circumstances where share prices might move in opposition to fundamental factors (earnings have largely stagnated since the middle of 2012; prices have risen solely on multiple expansion), but in every single case where that occurs it leads inevitably to the "liquidity causing transactions that might not otherwise occur" explanation.

At the time, I observed that stocks tend to do very well in nominal terms when currencies collapse.

While statistics are a bit hard to come by, we know that the Zimbabwe stock index was actually doing quite well, relatively, up to 2007. In April 2007, the Zimbabwe Industrial Index (I didn't know it existed, either) had risen 595% already for the year. In the prior 12 months, the nominal return was 12,000%. Inflation for the period was estimated at only 1,729% per year, so it appeared like stocks were "winning" the race. It did not matter that unemployment had reached about 80%, or that official stats estimated GDP had more than halved from 2000.

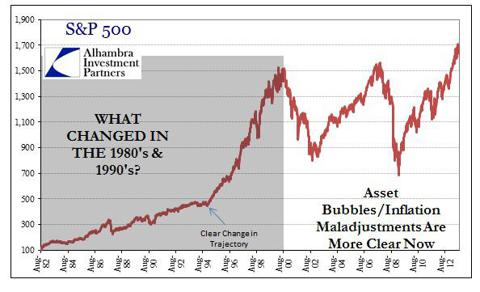

In the context of stock markets in assumed less "risky" locales, what are we looking at when Japanese and American stocks perform as they have? To me it is the Susan Bies explanation of "liquidity causing transactions that might not otherwise occur." And in doing so, that creates a lot of hidden risk, call it asset inflation or some other semantic construction, but it is not measured nor really appreciated in anything other than those longer-term performance numbers cited at the outset here. There is a price to be paid for such behavioral changes, what inflation really is in its most basic sense, and, for investors, this appears to be it:

Admittedly, this is still only a partially-formed construction, but there appear occasions, too numerous to simply ignore, where stock prices themselves reflect not "value" but risk itself. In the most absurd example, Zimbabwe, the higher prices went the greater the risks (eventual collapse). Stocks are not supposed to behave in such a manner, but it seems to have become somewhat commonplace as the chart immediately above more than suggests. We are taught to believe that higher prices mean something is more "valuable," but that intended axiom fails to apply in so many occasions in this current monetary age.

Perhaps that was always the implanted problem of fostering a system of prices based almost exclusively on transactions, but for some reason since the Great Inflation it has been heightened and expanded in both scope and scale. There are very close ties between "liquidity causing transactions," economic dislocations and longer-term malaise, and stock prices reflecting embedded yet unseen risks.

This entry passed through the Full-Text RSS service — if this is your content and you're reading it on someone else's site, please read the FAQ at fivefilters.org/content-only/faq.php#publishers.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire